by Dewey M. Caron, Communications and Content Specialist for the Oregon Master Beekeeper Program

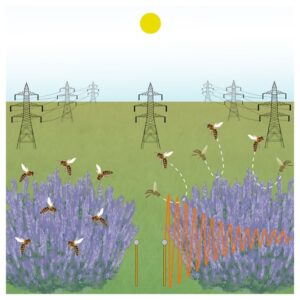

Bees have a power line problem

Honey bees can detect and apparently respond to airborne electric fields. Overhead electric transmission lines have static electricity emissions, something humans might be able to feel with body hairs. A research project in England created different electric fields around catmint plants to determine if foraging behavior changed. Using a weak alternating current (AC) reduced honey bee landings by 71% compared to a nearby control plant. The effect was most noticeable initially but the modified plant environment dis have an effect on foragers. In another test a DC current was used and foraging was reduced by 55% in this situation.

Honey bees can detect and apparently respond to airborne electric fields. Overhead electric transmission lines have static electricity emissions, something humans might be able to feel with body hairs. A research project in England created different electric fields around catmint plants to determine if foraging behavior changed. Using a weak alternating current (AC) reduced honey bee landings by 71% compared to a nearby control plant. The effect was most noticeable initially but the modified plant environment dis have an effect on foragers. In another test a DC current was used and foraging was reduced by 55% in this situation.

They were able to demonstrate that weak localized anthropogenic E-fields, comparable in strength to those measured tens of meters away from high-voltage transmission lines, alter honeybee foraging behavior. Honeybees exhibited reduced landing in response to both AC (50 Hz) and positive DC E-fields. By contrast, negative DC fields had no measurable impact on landing behavior Their conclusion: “It is therefore conceivable that anthropogenic E-fields, such as those produced by high-voltage transmission lines, could influence the foraging behavior of pollinators and their interactions with flowers.”

Diversity is best for bees

Dr. Susan Fluegel, a Nutritional Biochemist with a MS in Entomology, co-owner of Plow Maker farms, Colfax, WA, planted habitats featuring plant species of varying architectures to determine which could influence pollinator abundance and diversity. Her plant selections were intentionally selected for traits such as drought tolerance, long blooming periods, and low maintenance in the PNW region. Her project was supported by a Western SARE Farmer/Rancher grant.

Dr. Susan Fluegel, a Nutritional Biochemist with a MS in Entomology, co-owner of Plow Maker farms, Colfax, WA, planted habitats featuring plant species of varying architectures to determine which could influence pollinator abundance and diversity. Her plant selections were intentionally selected for traits such as drought tolerance, long blooming periods, and low maintenance in the PNW region. Her project was supported by a Western SARE Farmer/Rancher grant.

She demonstrated that a variety of plant species could significantly influence both the diversity of visiting pollinators and their numbers. She says: “just a few carefully chosen plants could sustain hundreds, sometimes thousands, of pollinator visits.” Her assessment method used time-lapsed photography taken every two seconds. Her booklet Increase Crop Yields by Managing Pollinator and Beneficial Insect Habitat in the Pacific Northwest. https://projects.sare.org/media/pdf/I/n/c/Increase-crop-yields-by-managing-pollinator-and-beneficial-insect-habitat-in-the-Pacific-Northwest.pdf is loaded with information on which pollinators it will attract and planting/cultivation tips.

Queen excluders: love them or leave them?

Best Management Practices (BMPs) should ensure both the health of the colony and the productivity of the hive. So is use of a queen excluder (QE) a BMP? Do you feel that a queen excluder might impede movement of worker bees in the hive or change the hive environment and you don’t care to use them?

Best Management Practices (BMPs) should ensure both the health of the colony and the productivity of the hive. So is use of a queen excluder (QE) a BMP? Do you feel that a queen excluder might impede movement of worker bees in the hive or change the hive environment and you don’t care to use them?

We know worker bees after receiving nectar from a forager seek a quiet place to begin active evaporation of the nectar in their honey stomach. The optimum passive evaporation of ripening honey might be altered by the type of hive used or with use of extra pieces like queen excluders and spacers. Queen excluders have been considered as honey excluders. Maybe you “hedge your bet” by using queen excluders early at initial supering and then remove them as the bees begin putting ripening honey into the supers you have added above the brood nest?

A 4-year participatory on-farm experiment, assessed the effects of queen excluders on colony dynamics in 64 hives, 32 hives managed with and 32 hives managed without QE, in 8 apiaries in Germany. The found: “ ……… queen excluders do not negatively impact honey reserves, brood size or the adult worker bee population.” https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13592-023-01041-9

Queen excluders might be used to strictly separate brood from honey frames, harvest honey from scarce floral resources, rear queens in queenright colonies, keep colonies with double queens or limit brood production. They have been tried as swarm emergence barriers and to confine/sample drones in colonies. Is a single season ‘s data likely to be the final answer? If you use them or don’t use them here is some ammunition for continuing the discussion with your fellow beekeepers ‘To bee (using queen excluders) or not bee (using them)!

Temperature stress

When it gets hot we are advised to hydrate. Among other benefits, proper hydration helps make sure our organs function properly, helps improve our brain function, helps regulate our temperature, and helps with digestion. ARS Researchers find that hydration is also the key to bee survival in hot and humid environments. They used bumble bees in their study of desiccation stress.

When it gets hot we are advised to hydrate. Among other benefits, proper hydration helps make sure our organs function properly, helps improve our brain function, helps regulate our temperature, and helps with digestion. ARS Researchers find that hydration is also the key to bee survival in hot and humid environments. They used bumble bees in their study of desiccation stress.

“For insect pollinators like bumble bees to survive and reproduce, they need to maintain an adequate hydration level,” said Karl Roeder, Research Entomologist at the North Central Agricultural Research Lab in Brookings, SD. “Erratic weather patterns have the potential to increase the rate at which insects lose water.”

Bumble bees survived three times as long in the coolest temperatures as they did in the warmest temperatures, with no effect of humidity on survival time. However, they lost water much faster in warmer and drier environments. Honey bees control their hive environment but presumably foragers might be subject to the same stress as the bumble bees.

Jamieson C. Botsch, Jamieson C., Jesse D. Daniels Jelena Bujan and Karl A. Roeder. 2025. Temperature influences desiccation resistance of bumble bees, J. Insect Physiology 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2024.104647